Late in the 1980's, before the Zymoglyphic Museum existed, I had an idea to make an aquarium, not with water, but a scene with a sandy bottom. This would be a big version of the surreal scenes in

sandtrays that I had been making at that time. I was recently married then, and the theme was of two fish making a home in a strange world. I liked the idea that the result would be a piece of furniture you would have in your house, rather than a piece of art intended for a pedestal in a gallery. It was even rather practical, in that it would be very low maintenance for an aquarium. The aquarium was made of various things that I had found and had been given. My wife was making intricate

hinged fish out of metal and plexiglass, and I thought an aquarium would make a nice home for some of them.

Even the title, "The Quiet Parlor of the Fishes", is a found object, taken from Thoreau's "Walden":

I cut my way through a foot of snow, and then a foot of ice, and open a window under my feet, where, kneeling to drink, I look down into the quiet parlor of the fishes, pervaded by a softened light as through a window of ground glass, with its bright sanded floor the same as in summer; there a perennial waveless serenity reigns as in the amber twilight sky, corresponding to the cool and even temperament of the inhabitants. Heaven is under our feet as well as over our heads.

"Walden" was one of my favorite books in high school. It provided a mythic and spiritual dimension to nature that transcended the mere collecting, naming, and classifying of specimens, which had been the focus of my

original museum. The summer between high school and college, I even tried a brief emulation of Thoreau's year-long stay at Walden pond. I camped out by myself for four days on an island in the middle of a small mountain lake in Olympic National Park. I paddled out to the island on a primitive boat made by tying driftwood logs together, read Walden, and wrote a short journal, trying to emulate Thoreau's 19th century style.

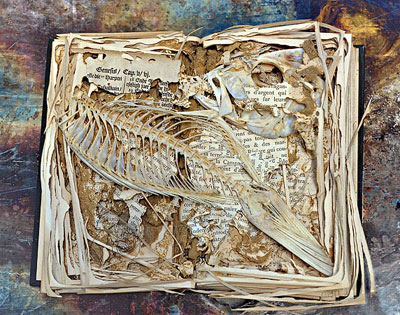

In this dry aquarium, the two fish have a little television set in their parlor and are watching a program that features one of the Judy's art-fish. They also have their own little dry aquarium, foreshadowing the worlds-within-worlds theme of the museum-to-come. This first aquarium was followed by a series of small

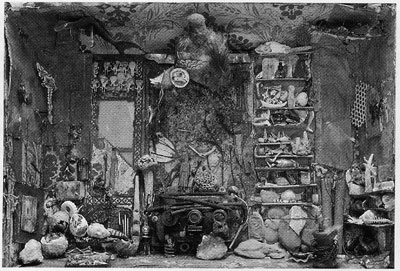

dioramas inside standard 10-gallon aquariums. Some had a terrestrial theme and some were aquatic. The serenity of the underwater world, eternal and unchanging, gave way to the archetype of the primordial ooze, a crowded, dense, active, messy world of creation, decay, and conflict, and a Walden-like mythological cycle of death and rebirth.

In recent years, I have been trying to capture a sense of the little worlds inside the dioramas in close-up photography and I think this is one of the more successful attempts. It is the little aquarium in fishes' parlor. This picture was, in fact, my entree into hallowed halls of the

Museum of Dust.

In the past couple of months, Judy has been

experimenting with pinhole photography, using homemade mini-cameras. I was not convinced of the true potential of this technique until she took some photos of the aquarium, which gave the whole thing a dreamlike air. The full set of photos can be seen

here. One of the those photos, of an astronaut from the moon who is coming to visit the fish, resulted in her own

initiation into the Museum of Dust.

Labels: Dioramas, Museum objects and collections, Photography

As I noted

As I noted  A lesser-known type of work that he does are "snowball paintings", which are created by putting a snowball stained with a natural dye on paper and letting it melt. The result is an amazingly detailed pattern created by the way the dye is deposited as the snow melts and the water evaporates. A detail from one is shown here, with an enlargement

A lesser-known type of work that he does are "snowball paintings", which are created by putting a snowball stained with a natural dye on paper and letting it melt. The result is an amazingly detailed pattern created by the way the dye is deposited as the snow melts and the water evaporates. A detail from one is shown here, with an enlargement