How the museum came to be |

|

Early influences

My father was a naturalist, and I used to tag along on his field trips. I especially remember the ones to the tide pools, which seemed like the edge of a vast unknown world. I looked once into a stereo microscope at a selection of creatures from the sea - a completely strange and alien world, yet undeniably real. Another favorite destination was the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, with its dioramas and collections of strange frogs and lizards. I especially liked the smaller, more intimate dioramas.

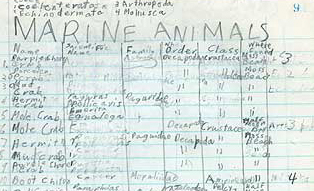

I presided over my own little museum and zoo when I was a boy. It was mostly natural history - rocks, fossils, beetles, bird nests, shells and other marine life. There were also chemicals, arrowheads, astronomical charts, and a stamp collection. They were all identified, labelled, and catalogued - see the sample page shown here. I liked the idea of being an "amateur naturalist."

I presided over my own little museum and zoo when I was a boy. It was mostly natural history - rocks, fossils, beetles, bird nests, shells and other marine life. There were also chemicals, arrowheads, astronomical charts, and a stamp collection. They were all identified, labelled, and catalogued - see the sample page shown here. I liked the idea of being an "amateur naturalist."

When I was 14, I went with my family on an extended car tour of Europe. Many of the highlights for me were the museums, whose contents I listed in great detail in my diary of the trip. One image from the trip that stands out in my mind is a gigantic spider crab mounted on the wall of the Oceanographic Museum in Monaco.

In high school and college, I drifted away from the sciences, since I knew that I would have to choose a specialty, and I found all aspects of science equally fascinating. Literature and soft sciences such as sociology and psychology offered the promise of insight into the meaning of life, which science, being literal and descriptive, did not.

One new interest was art, especially surrealism, which I took to immediately. It made strangeness significant and even legitimate. I also got absorbed in mythology, Jungian psychology, and science fiction, enjoying stories of other worlds and supernatural forces. I had no religious background, so these ideas seemed to fill a void.

We had a short-lived "Fred Gallery" at college, from a standing joke: "Is it Art? No, it's Fred". The gallery was in an unused phone booth in the dormitory. People would contribute objects like dead roaches or old food that had gotten weird. It was an ironic and humorous approach to art.

Creative stirrings

As I later pursued careers in health care and computers, some events occurred that awakened my creativity. In my mid 20's I found a piece of driftwood that looked to me like a miniature landscape. I added some shells and small crystals to it to enhance the effect. One object I added was a limpet shell that seemed to look like a little cathedral. Later, I put an old clock on a plant stand and added a doll arm and a crab claw to create my own "surrealist object."

I liked to hang around artists during this time, but I did not think I was creative enough to actually be one. By my mid-30's I had collected a number of objects that were souvenirs of trips and odd things from thrift stores, including a number of large, strange ashtrays. I filled the ashtrays with sand and started arranging souvenirs and items from my old collections to make miniature surrealistic landscapes - one of them is shown here. My tiny bachelor apartment was soon filled with these creations. Around the same time, I started putting together the first narrative scene, called "Bug Wars", starring some little beetles and sewing machine parts, creating a post-apocalyptic drama pitting insects against machines.

I liked to hang around artists during this time, but I did not think I was creative enough to actually be one. By my mid-30's I had collected a number of objects that were souvenirs of trips and odd things from thrift stores, including a number of large, strange ashtrays. I filled the ashtrays with sand and started arranging souvenirs and items from my old collections to make miniature surrealistic landscapes - one of them is shown here. My tiny bachelor apartment was soon filled with these creations. Around the same time, I started putting together the first narrative scene, called "Bug Wars", starring some little beetles and sewing machine parts, creating a post-apocalyptic drama pitting insects against machines.

My involvement in the art world got closer when, at 38, I married an artist. She was creating small fish at the time, made of metal, plastic, and found objects. By then I was creating scenes on the mantelpiece and scenes in bookcases. I had an idea of creating an aquarium-like environment for some of Judy's fish. The result was a large, dry aquarium on a stand. I liked the idea of creating something that was an integral part of your living environment, rather than primarily for a gallery or museum. At about the same time, we got a cat and "Bug Wars" needed to be protected. So I built a clear plastic box for it and it became the first official diorama.

My wife and I lived in a flat in San Francisco's Richmond District. I set up a studio in a little room in the garage and started collecting interesting objects and arranging them in 10-gallon aquarium tanks until they seemd to "glow". The quality that I looked for in the things I collected was usually something that suggests something other than what it is. An example would be a discarded candy wrapper that, when turned in a certain direction, looks like a particularly strange mushroom. I was putting objects together intuitively, as suggested by the material, with no plan for the final outcome. The "glow" had something to do with balanced (but asymmetrical) composition and a mysterious but compelling narrative quality, a sense that there was an interesting story going on. Later, I did make up stories for my little dioramas.

Getting serious as an artist

I was still not convinced that what I was doing really qualified as "art". I liked the idea of dry aquariums because they could be seen more as furniture or household decoration rather than having to qualify as "art", or, even worse, "good art." I was neither a painter nor a sculptor, but there was a category in art called "assemblage" that seemed to fit what I was doing - taking existing objects an putting them together. However, assemblage artists generally do not make miniature scenes, so I was in my own genre. This was good because again there was nothing better or worse to compare my work with. Even if people didn't like it or couldn't relate to it, they could say "Well, I've never seen anything like that before!"I finally decided to declare what I was doing as "art" and that I was an "artist" by joining Open Studios of San Francisco. Open Studios is open to anyone who wants to participate, and you can have people come to your home to see your work. This worked well for me, since I did not have to worry about being "accepted" and my work could be seen in its natural environment. I particpated in Open Studios every year from 1989 to 1993. I usually presented my work as "exhibits from some imaginary natural history museum". The feedback I got was generally much more encouraging than I had expected.

The museum opens

In 1994, we moved to a house in San Mateo. My wife had developed a dust and mold allergy that made it undesirable to keep a lot of little (undustable) objects and organic matter in the house. Fortunately, the house has a particularly long driveway and we were able to have a shed installed in it. This building became the exhibit area and the Zymoglyphic Museum had its grand opening in April of 2000. By that time I had also set up the Web site and had begun thinking of my work in the context of an imagined world with its own history, artifacts, and mythology. In the role of museum curator, I have an alter ego to duck behind if I feel the need to be anonymous.I have done Open Studios every year since the grand opening. Attendance is often sparse (about 20 people per weekend) but there are always some people enthusiastic enough to make it worthwhile. That and the Web site are my main ways of presenting my work to the world and getting feedback from others. My hope is that others will be able to find ways to express themselves creatively without worrying about having traditional art skills, or whether what they do fits into some established pattern.

So, in the end, it seems I have recreated my old museum, but this time it is my own personal expression, moving from a literal interpretation of nature (collecting, naming, arranging by scientifically determined category) to arrangement by intuition, symbolism, and aesthetics. Both of them originate in an appreciation of nature in its dizzying variety and basic interconnectedness. The new museum goes beyond the literal realm where science must stop, to a more symbolic realm and ultimately a sort of personal cathedral.

For more stories on the history of the museum, see the Curator's Web Log.